A weird youth, I picked up Dante’s Inferno at 15, partially because it was about Hell, partially because I liked the cover. It would be decades before I wandered into my own dark wood mid-way through life’s journey, but the teenaged Greg haunted the poet’s steps as he picked his way through the circles of damnation until he reached the bottom and Lucifer, himself. (Most shocking to me at the time, and still, was that the greatest archetype of evil in Christian cosmology weeps, despairing at his exile from God.)

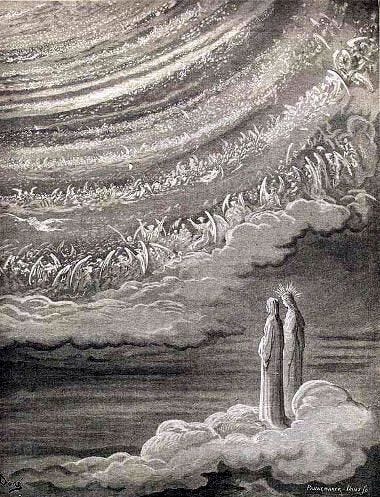

Only in adulthood did I read Purgatorio and Paradiso, works as glorious as the first installment of the Divine Comedy, but more subtle and, at least in the case of Paradiso, more outrageous in terms of Dante’s personal theology. The pilgrim ascends to the height of heaven and there he sees the Mother of God at the center of a cosmic rose where sit the blessed, as the angels, like heavenly bees, fly between Mary and the ineffable mystery of God. A good Catholic, Dante reveres the Divine Feminine.

It’s a good time to revisit Dante’s heroic journey. The tale begins on Good Friday, coming up next week, and goes through Easter to the days beyond as the poet reaches heaven. The poem is both an admonishment and an inspiration, warning us how close we are to perdition, inspiring us with what awaits the soul who humbly acknowledges its darkness.

I’m not talking about Catholic doctrine, which, for the most part, is garbage. I’m talking about the metaphysical journey of the spirit and the knife’s edge between despair and hope. The worst sin in the Catholic universe (and there is a catalogue of wickedness) is despair, the belief that we are completely lost to God. The figures in Dante’s Hell suffer despair for eternity, the ultimate torment in a vision of the damned that still harrows the imagination.

How do we think of sin and despair in a truly spiritual, not religious, context? Sin is missing the mark, coming from the Greek word hamartia, related to archery. Hamartia, in Greek drama, is the the protagonist’s tragic flaw. Oedipus’ tragic flaw is hubris, arrogance in the face of the gods; he can’t imagine that he’s the problem. This is how he “misses the mark” - his ignorance of his own foolishness blinds him to clear sight of himself.

Dante, chagrined, recognizes his own purgatorial circle where he will suffer most, the circle of pride where sinners stoop under the burden of heavy stones. His sin, the one most keen, is his tragic flaw, and yet, in the Medieval Christian context, he will be cleansed of it, because he knows it, acknowledges it, and repents of it, repentance relating, ultimately, to the Latin poena, recompense, expiation, penalty, retribution.

If we don’t recognize our tragic flaw, our sin, if we don’t make recompense for it – an act of admission and change of behavior – it’s then we fall into the dizzying circles of the pit, it’s then we’re trapped without hope of redemption, not because of some outward patriarchal proctor, but because of our own unwillingness to reflect on who we actually are. Too often in “spiritual communities,” words that have lost all potency through overuse, we focus on the light, the light body, our limitless capacity for love, our connection to divinity, blah, blah, blah. What we forget is its correlative: the darkness, the trauma body, our limitless capacity for cruelty, our connection to the demonic. All of this happens within the soul, within the mind and heart. Hell, Purgatory, Heaven, it’s all inside our consciousness, individual and collective, and the only God to forgive us our sins is the one within us.

As we approach the Christian Holy Week, consider reading the Divine Comedy, and take that dark and savage road into one’s own Hell where we abandon all hope. Get comfortable with the monsters inside the soul. Traverse the plains where fire rains down; pick your away across the ledges which soar above sinners up to their eyes in excrement; march past the hypocrites, cloaked in bedizened robes that are lined with lead; creep past the sowers of dissent rent in twain, miraculously healed, then rent again. Only then will you reach the heaven inside yourself. The reward of paradise is not possible without the punishment of perdition. Be thankful for your sin, your hamartia, and then be thankful for the grace of self-reflection. Armed with contemplation, you’ll know the full universe inside yourself, you’ll recognize that you are God, that you are the love that moves the sun and the stars.

All the images are by the famed Gustave Doré.

One of my favorite translations of the Inferno is by Robert Pinsky. The Purgatorio and Paradiso of Jean and Robert Hollander are solid in their poetry, but brilliant in their accompanying notes.