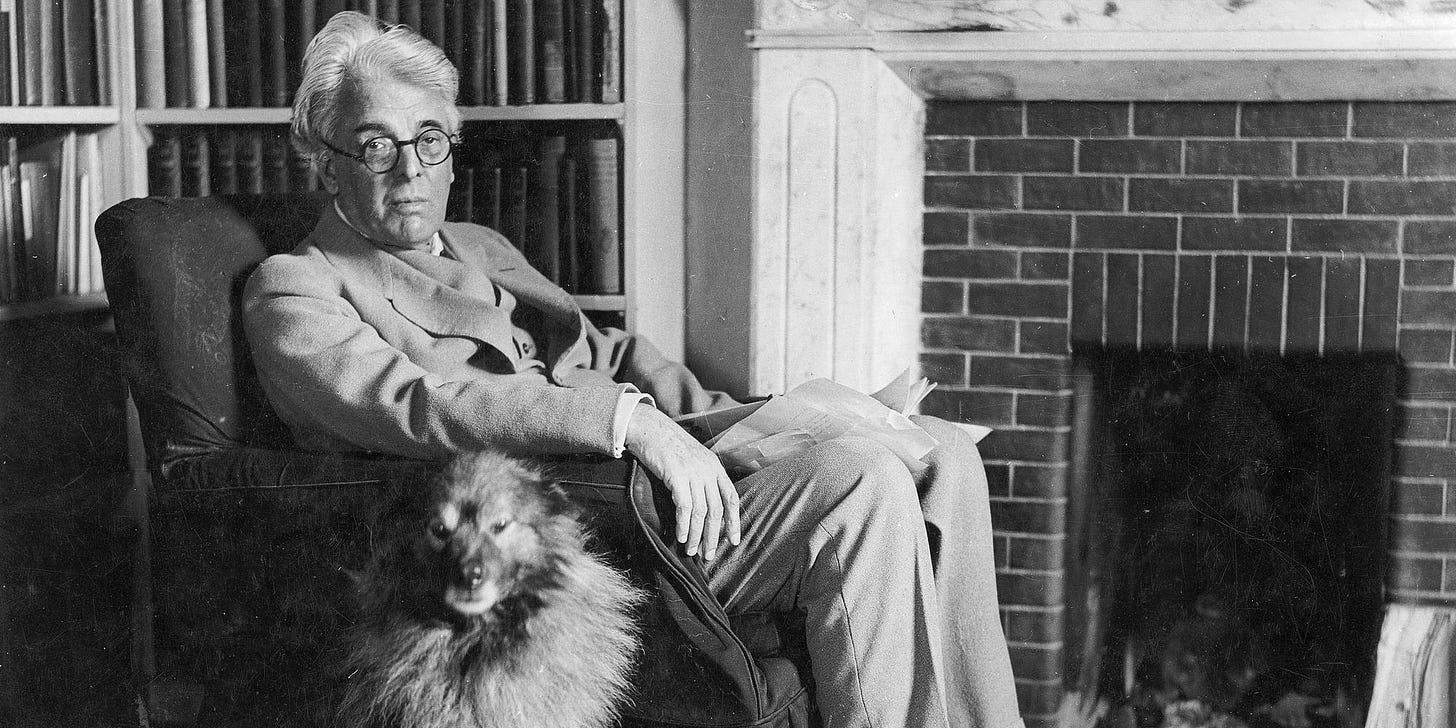

On this St. Patricks’ Day, I think not of the righteous saint who drove the snakes out of Ireland (“adder” sometimes a name for members of the Druid order so that the Christian boor exiled wisdom from the Emerald Isle), but of one of my favorite poets W.B. Yeats. Steeped in myth and mysticism of a dizzying (and sometimes stultifying) complexity, as well as pride for his native Ireland, the late 19th-, early 20th-century poet stands as a last remaining master of the bardic arts – the ability to weave stories with deep reflection, enchant with sound, remind us of our aching humanity, infuse our daily lives with his poetic perceptions that somehow seem like our own. Many are the Yeats poems I have by heart, and while it’s tempting to use this post for The Second Coming, the slouch (or is it a gallop now?) towards Bethlehem seems a little on the nose, so instead we’ll look at The Song of Wandering Aengus.

I went out to the hazel wood, Because a fire was in my head, And cut and peeled a hazel wand, And hooked a berry to a thread; And when white moths were on the wing, And moth-like stars were flickering out, I dropped the berry in a stream And caught a little silver trout. When I had laid it on the floor I went to blow the fire aflame, But something rustled on the floor, And some one called me by name: It had become a glimmering girl With apple blossom in her hair Who called me by my name and ran And faded through the brightening air. Though I am old with wandering Through hollow lands and hilly lands, I will find out where she has gone, And kiss her lips and take her hands; And walk among long dappled grass, And pluck till time and times are done The silver apples of the moon, The golden apples of the sun.

The poem first appeared in his 1899 collection, The Wind Among the Reeds, and Yeats said the name in the title refers to “The God of youth, beauty, and poetry. He reigned in Tir-nan-Oge, the country of the young.” Not just the title, but the entire piece is infused with Irish symbolism and magic.

Hazel trees are considered sacred in the country’s pre-Christian lore, so from the first line, we’ve stepped out of mundane time, the world of cars and bills and groceries, and through the door into legend. Aengus leaves for the wood because a fire is in his head. To be burned inside-out, to suffer the heat of creativity, of mystery, of wonder while living in a society built to smother the blaze, to keep us in line, to suffocate not only our individuality but our access to expanded consciousness be it artistic or mystic (no difference, I’d say), to be that kind of an exile means that for your own sanity you must run to the green world, into nature where all seems, if not right, at least comprehensible. The mad world is the one frequented by what Quentin Crisp called “the dead normals;” the world they consider mad is the only place where you can survive.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dancing With the Black Madonna to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.